CPR and Canada’s First Nations: A Study in Contrasting Contracts

Between 1870 and 1880, two events, seemingly unrelated, had profound effects on the development of Canada, with each demonstrating a starkly different understanding and application of respect. Both were undertaken with the objective of expanding the new nation of Canada, both involved cash payments and land transfers, yet each showed how the fledgling country viewed rights. The first was the contract between the government of Canada and the Canadian Pacific Railroad, to develop a rail line that would reach to the west coast of British Columbia, with its non-indigenous population at a mere 12,000 or so, bringing it into the Canadian family. The other was the undertaking of a series of eleven treaties with the Noth American Indians, primarily in Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan, with Manitoba joining Confederation in 1870.

The CPR saga was, in its own way, a quagmire. British Columbia agreed to join Canada in 1871 with the promise of a cross-Canada railroad linking the country from east to west, but the original contracts with Hugh Allan were mired in scandal and it was not until 1880 that the CPR signed a contract to undertake this massive project. The government of Canada contracted to provide $25 million to the railway and 25 million acres of land in western Canada. The right to the acreage extended 24 miles on either side of the rail line. This was in addition to a donation by the Canadian government to CPR of a $25 million section of rail line in Ontario, portion of a rail line in B.C. and tax-free status until the company is sold. (Note: In 1966, that clause was waived)

That cash value, in today’s money, is more than $1.6 billion. The land value, much of which was either prime agricultural land or prime urban development land may be worth much more than $15 trillion, if every acre was average farmland and not prime agrarian or urban property. Indeed, the contract allowed CPR to reject substandard land (marshland, waterways and land not acceptable to the company)

Other terms of the contract allowed for non-compete clauses that were extraordinary.

Indeed, the original contracts between the Canadian government and the CPR were often not fulfilled by the CPR on deadline (nor was the Canadian government promise to have a railroad completed by 1881), but the government allowed CPR to bypass or extend deadlines and ignored quality of sections of the railroad that was suspect. The line was not fully operational until 1886.

While the railroad has proven to be an essential undertaking for the country, its development contrasts sharply with the contracts—treaties—the government entered into with the First Nations between 1871 and 1921, with the second last of the eleven treaties with prairies’ First Nations signed in 1906. The first six, signed before the Indian Act in 1876, were the most noteworthy and were the most flagrantly violated by the government.

At the time of Confederation, there were an estimated 22,000-35,000 Indians in western Canada. No accurate data is available, because the First Nations were not tabulated in any government census of the period. The population had been decimated by disease and famine (more on that later) in the prior thirty years, and the Indians were desperate for assistance.

But let’s examine a little historical context before we delve into the specifics of the First Nations initial 6 treaties.

Of course, talks about our western pioneer days would not be complete without reference to the vast herds of bison that roamed the Great Plains prior to 1800. At their peak, bison numbers were estimated at between 30 to 60 million head, of which 6-10 million lived in Canada, including the wood bison of the northern prairies (a smaller species of bison compared to the plains bison).

In Canada, by 1900, there were fewer than 300 animals. In 1870, estimates of the herds in North America placed the count at 5.5 million. By 1875, that number was 395,000.

What happened? White settlers and American policy largely were the causes.

While President Grant did not explicitly order the killing of the bison to effect the genocide of the American Indian, he let the legislation protecting the bison die without signing it into law. This guaranteed the decimation of herds. The Manifest Destiny doctrine, which espoused American domination of everything in North America, sought to eradicate the First Nations population to enable white settler ascendency of the west. Elimination of the buffalo was key to this strategy.

These policies and actions encouraged continued slaughter of the bison in the US and genocide of the American Indian.

North of the 49th, the practices of the Northwest and Hudson Bay Companies may have seemed more benign and less genocidal, but their practices had the same result: the decimation of the “buffalo” herds on which the Indians relied as a food source.

Stealing the First Nations’ idea of pemmican as a vital food supply, fur traders and even settlers dried hundreds of thousands to millions of pounds of bison meat with fat and berries to use as an essential survival food. Where the meat was not needed, furs were taken and carcasses left to rot. It was ironic that a native recipe that ensured their survival in winter was also the primary cause of their demise, or at least the famines that followed from 1850-1880.

With no mainstay nutrition in the winter, and extremely scarce meat supplies in the summer, they starved, with populations of First Nations peoples dropping from the millions in the 1700s to as few as 100,000 in 1800 in Canada, then around 22,000-35,000 in western Canada by 1870. It was a practical genocide in the USA but a passive culling in Canada.

Famine, though, was not the only scourge for the western Indian. Disease, too, killed many. Smallpox, for which the natives had no natural resistance, killed far, far more Canadian First Nations than violence.

There are many Americans and Canadians who see the interaction of white people with Indians across the west as a violent conflict, sometimes referred to as the Indian Wars. Yet this is a uniquely American interaction.

In fact, in western Canada, the only violence in which First Nations people were involved almost always occurred Indian to Indian, at the encouragement of white fur traders who were seeking advantage in the lucrative trading business of the Northwest and Hudson Bay companies. In a few rare instances, Canadian Indians were encouraged to battle with US Sioux and Indians from the Dakotas, again, for the benefit of the white settler. The Metis uprising began with the interaction with the two dominant trading companies.

Canada’s history with our aboriginal population, particularly in western Canada, was one of assimilation and intermingling, with coureur des bois and white settlers taking Indian wives.

Even more in contrast to the American version of interaction (domination, in actuality) with Indians, the First Nations north of the 49th more often assisted the settlers and trappers to acclimatize to Canada’s rough winters, helping them in any way possible. In return, they were taken advantage of and diminished by those white invaders.

Two stories stand out in Manitoba: Chief Peguis and John Ramsay.

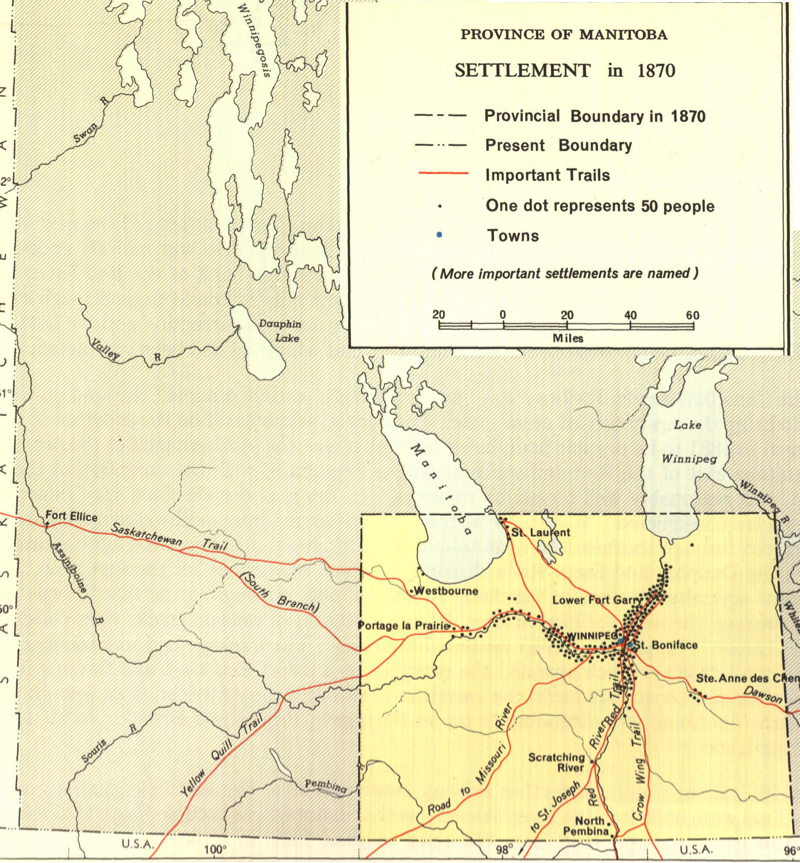

Around 1876, while the first few contracts with the aboriginal population were taking shape in Manitoba, several events occurred concurrently. First, Manitoba joined Confederation in 1870, known as “the postage stamp province” for its small, rectangular boundaries at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. In October, 1875, arrived, just before winter set in. The Icelandic immigrants to the area were granted jurisdiction over a large swath of land along Lake Winnipeg’s west shores, from Boundary Creek, south of today’s town of Gimli, to an area along Hecla Island, where the north and south basins of Lake Winnipeg meet. It was known as New Iceland territory, a part of the Northwest Territory.

The Manitoba territory encompassed the prime agricultural land in the province, but also was the traditional meeting place of many of the First Nations tribes every summer. They were squeezed off the land.

The New Iceland territory was the traditional hunting and fishing area of several native tribes, who were driven further north.

While the provincial region had been slowly ceded by the Indians following an 1817 informal treaty negotiated by Chief Peguis (a Saulteaux First Nations chief who had migrated from Ontario), no such informal or formal agreement encompassed the Gimli acquisition and grant. The tribes simply were slowly forced to give way.

Enter John Ramsay, a First Nations Ojibway who hunted, fished and lived along Lake Winnipeg’s southwest shore.

The year that the bulk of the Icelandic settlers arrived from Ontario, Manitoba experienced one of its most brutally cold winters. In spite of being from a country named “Iceland,” these white immigrants had never experienced the harshness of a prairie winter and knew very little of how to trap, forage, hunt or fish. Particularly how to ice fish.

John Ramsay had met white people for many years prior, but these were a unique people. He adopted them, helping to teach them how to survive and even providing food for them. At the same time, the smallpox outbreak was rampant in the community.

Ramsay ultimately lost his beloved wife, Betsey, and three of his four daughters to the disease. His fourth child remained horribly scarred by the pox. Nonetheless, he continued to help the Icelanders and has been credited with saving many white lives that year.

How was he rewarded? He was forced off his traditional land, northward. Then he was forced off that territory by white settlers, and he joined the Peguis band.

Chief Pequis was equally interesting and deserving of our admiration.

He had moved his Saulteaux tribe from the Sault area of northern Ontario westward in the late 1700s. He worked as a guide for the fur traders and was instrumental in negotiating a treaty in 1817 that allowed white immigrants to expand settlements where Selkirk and Winnipeg now stand.

He died prior to 1871, when his son signed Treaty 1, providing a reservation for his band near the town of Selkirk. It was prime agricultural land, and when the government realized its value, the Peguis band was compelled to relinquish the land and move 100 km north, to virtual scrub land with a history of flooding. White settlers took over the valuable farming area. Pequis’ reward for his loyalty and support of the white immigrant was banishment of his band to the farther reaches of the province.

A third series of events was equally telling as to how the white government viewed the Indians, Indian traditional rights, respect for the First Nations and fairness.

The Sioux Indians were relatively nomadic, ranging from the Dakotas to areas along the Assiniboine River in Manitoba’s southern area. Most of the Indian bands were semi-nomadic, moving seasonally. In truth, the whites also moved into and around the province, with unfettered access to the Dakotas and Canada. Many Icelanders moved from Gimli to Minot (North Dakota) and back again without impediment.

Yet the government of Canada interpreted that the Sioux were not “Canadian,” but, rather, “American,” even though the Indians knew no 49th parallel boundary. It was arbitrarily imposed on them.

As a consequence of the government’s interpretation of the Dakota Indians being American, they were denied the right to treaty agreements and treaty land, until 1972.

So, we have taken a cursory look at the background to the interaction between First Nations people of the prairies and the Canadian government prior to the first of the 11 treaties entered into with the various tribes. This sets the stage for the fairness, or lack thereof, demonstrated in the first few treaties signed during the critical pioneer period.

The first seven, with Treaty 7 implemented in 1877, encapsulated the interaction with and arbitrary nature of the government in dealings with the First Nations of Canada and the Indian Act of 1875-76.

The Indian Act seems to blatantly strip First Nations of their rights and celebration of their own way of life and culture, contrary to the spirit, if not the letter of each of the first six treaties.

It sets out requirements for Indians to be assimilated into Euro-Canadian culture and for them to be stripped of the right to celebrate their own culture, speak their own language and live in a manner that has been their historic way of life for centuries. It bound the First Nations people to their reserves. It, and other Acts, such as The Gradual Civilization Act required Indians to speak, write and read either English or French. That was supported by the 1869 Gradual Enfranchisement Act, which required Indians to assimilate into Euro-Canadian culture. Interestingly, only one person voluntarily did so. The Indian Act, although modified, still remains in effect in Canada.

In spite of the guidelines of these two antecedent acts, the government of Canada entered into treaties prior to 1876 that extended autonomy of the First Nations communities on reserves, then unashamedly ignored those rights.

Treaties 1 & 2 (1871) covered an area of land from the 49th parallel to Oak Point and down the west side of Lake Manitoba, through Portage to the US border, which the Indians “ceded” to the Dominion. In return, they were promised $3 per person per year (goods and cash, at the discretion of the government), a few implements and traps and the right to reserve territory amounting to 160 acres per family of five. This included relinquishing most of the new province of Manitoba, but the Indians were granted the right to hunt and fish on all unoccupied Crown lands. That right often was disregarded by the government.

Mostly, the sites of the established reservations were arranged with the impacted bands but influenced by the government negotiators.

Treaty 3 provided for an initial payment of $12 per family of five plus $3 per year. In exchange, the First Nations bands ceded 55,000 square miles of land (35.2 million acres) and were granted no more than 640 acres per family of 5. In perpetuity, they were to be paid $5 per head. They were compelled to give up millions of acres in exchange for less than 15,000 acres of substandard land and $24,000 of goods and cash.

Treaty 4, in Saskatchewan, raised the bar a little, providing $5 per head and farm implements, but, while the government could sell the land, the Indians could not.

This was the first treaty that discussed infrastructure, such as roads. Until it was signed, the government did not claim a right to build roads and run infrastructure through the land, yet they usurped that right anyway.

Treaty 5 (1875), like the prior treaties, required the government to provide schools on the reserves when the Indians wanted them.

In four years, treaties had been signed with about half of the First Nations from Lake Superior to the foothills. But every one of the treaties was not fully fulfilled or adhered to by the government. This included the failure to provide the land promised, and providing land unsuitable for the purposes intended. Today, many court cases revolve around unresolved land claims pursuant to these first treaties.

Several of the treaties provided for farm implements and limited livestock to be provided to the natives, along with medical supplies. Many of those same reservations were situated on land wholly unsuitable for agriculture. Many of the reserves today are on marginal lands, lands prone to flooding, lands without proper access, lands that cannot grow a crop and lands cannot be developed. Yet the government demanded that the people on those reserves adopt a completely “Canadian” way of life.

One of the more disgusting examples of the government heavy-handedness is the Peguis Reserve in Manitoba’s Interlake. Its original site, near Selkirk, was prime agricultural land and, when white settlers wanted it for themselves, the government relocated the Indians 100km north to swamp and bush land.

Even as late as in the 1960s, Manitoba Hydro needed land on which First Nations held a reservation near Grand Rapids. Arbitrarily, the government divided the reserve up, sending some to a small community called Easterville. Families were split, homes destroyed. Moose Lake, too, was largely destroyed by the dam project. This project occurred on Treaty 1 land.

The history of government dealings with the prairies First Nations, as appalling as these few examples sound, is replete with a multitude of examples of broken promises or cruel treatment.

While many Canadians superciliously look to the American Indian wars and the treatment of Blacks, our own history should cause us shame, given the lack of respect that Canada has shown for the rights of its founding people, the indigenous populations.

The Supreme Court of Canada continues to hear cases surrounding treaties with our First Nations, but many of these challenges to the actions of the governments in the 1800s remain unresolved.

In the meantime, we hold up the contract with the government of Canada and the CPR as an example of how honourable we have been.

Today, the $24,000 given to the Indians in exchange for giving up 35 million acres is worth $594,000. Compare that to the $15-25 trillion dollar value spent to accommodate 12,000 white residents of British Columbia and entice them into Confederation.

That’s $1.7 billion per person. In exchange, the First Nations of northwestern Ontario were paid $216. Is that respect?